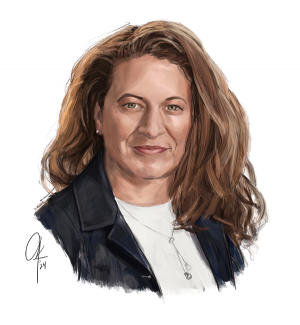

Meet the Expert: Karla López de Nava

Karla López de Nava studies health policy with a focus on Medicare payment models. She uses advanced statistical analyses to evaluate value-based care models on their design, operation, and implementation. Prior to joining AIR, she was a vice president at the Lewin Group.

POSITION: Managing Director

AREAS OF EXPERTISE: Medicare payments, value-based models, data analytics

YEARS OF EXPERIENCE: 15

Q: One of your focus areas is value-based incentive programs within Medicare payment policy. How do they work?

Karla: Traditional Medicare pays a fee for each service rendered. That gives health care providers an incentive to provide more services. As a result, the volume of services grows over time, and with it, Medicare expenditures.

To contain the rapid growth in Medicare expenditures and increase the quality of care, CMS has introduced value-based payment models, where the payment for services is subject to the quality of the care and cost savings. There are several measures that help determine quality: rate of patient readmission to the hospital; rate of hospital-acquired conditions; mortality; patient satisfaction, and so on. If the program finds a demonstrated improvement in quality and cost-savings, providers receive increased payments. Alternatively, if the financial and quality of care targets are not met, payments to providers might be adjusted downward. Either way, the incentive tilts away from volume of services toward value of services.

For the most part, participation in these models is voluntary, so establishing the right financial incentives is key to the success of these models. For example, if the financial incentives for providers are not correctly laid out, and providers deem that the risk is too great relative to the rewards, they can elect not to join. If there’s no participation, the model is by definition unsuccessful even if, in theory, it would have generated savings and improved quality.

Q: How are these models tested?

Karla: There are different kinds of contracts that relate to these models, and I have experience working with two kinds: implementation, operation, and monitoring contracts; and evaluation contracts, where we help CMS determine whether the models were successful in meeting its goals. They both have their advantages, and their uses. Implementation efforts tend to be faster paced, and flexible—they allow us to adjust the model in real time. For example, during the pandemic, CMS was willing to increase payments to providers and relax some of the required quality of care targets, basically adjusting the models in real time based on immediate circumstances.

Evaluation projects, on the other hand, tend to be slower paced and more retrospective, because they require sufficient performance data to conduct a robust evaluation—and with claims and administrative data, that can take some time to collect. However, that wealth of data provides really robust insights into the inner workings of the model, and help inform the design of future payment policy and models.

Q: What role does health equity play in value-based models?

Karla: CMS is prioritizing health equity, trying to incorporate it into the design of these models. This is a great goal, of course, but the problem is that we currently don’t collect good data on social determinants of health like race and poverty. In general, equity is a multisector problem, and only so many variables are under providers’ control. For example, if a patient has diabetes, their physician might recommend that they eat healthier food—but perhaps they do not have access or resources to acquire those recommended foods. That’s why CMS is being cautious with these programs and their design.

Although CMS’s priority is to make providers accountable for their patients’ health, CMS recognizes that many factors influence a patient’s health that aren’t in the provider or hospital’s control. For this reason, multi-pronged approaches, and cooperation across a wide swath of government agencies, are necessary to fully advance health equity and improve population health.

Q: What are some misconceptions around Medicare?

Karla: There are quite a few misconceptions around Medicare. Some people believe that it is free. Medicare Part A, which mainly covers hospital services, is free, because the beneficiary or a spouse paid Medicare taxes long enough while working. However, Medicare Part B, which covers physician services, and Medicare Part D, which provides prescription drugs coverage, involve a premium.

There’s also some ignorance around who is eligible for Medicare—for example, end-stage renal disease patients are eligible, regardless of age. Sometimes people assume that you’re automatically enrolled in Medicare when you turn 65, which is not true; people need to actively enroll. That is another equity issue—people lacking this knowledge will miss out on important benefits.

In general, I notice a lot of fear around government regulated and publicly funded health. People sometimes think that health regulation or public health insurance programs like Medicare and Medicaid mean communism or socialism, which is absolutely incorrect. In the U.S., our enterprise capitalist history has led to a for-profit health model. This is most obviously seen in the pharmaceutical sector, where drug prices are incredibly high compared to other nations, and regulating prices has been challenging. But health care regulation and government-provided health care would not result in communism; they would just put us in line with other industrialized countries where per capita health spending is lower and life expectancy rates are higher.

Q: How might the health care landscape look different in 10 years? In what ways might it look the same?

[I hope] that we will make some strides toward advancing health equity. In 10 years, if another pandemic strikes, hopefully the racial disparity in access to care and outcomes will be less severe.

Karla: The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation has set an objective—they want all Medicare beneficiaries with Parts A and B in some kind of accountable care, value-based model by 2030. I think that’s a little ambitious. But my hope is twofold: first, that more patients are aligned with value-based models and are able to receive more patient-centered care. The second is that we will make some strides toward advancing health equity. In 10 years, if another pandemic strikes, hopefully the racial disparity in access to care and outcomes will be less severe. That being said, those are my hopes, not my expectations. I also hope that the recent Inflation Reduction Act, which caps the prices of certain drugs, will gradually help lower overall medical expenses for patients. But I’m not expecting dramatic changes. Policy changes, especially in our divisive political landscape, tend to be small.

Q: Where can we find you on a typical Saturday?

Karla: I have three young kids, ages 10, 8, and 5. My husband and I both work, so Saturdays and Sundays are very precious opportunities to be with our kids. You might catch us all jogging around the neighborhood, or at an amusement park, or watching a movie at home.

Q: What book would you suggest anyone read?

Karla: Over the last 20 years, I’ve become a huge sci-fi and fantasy fan. If I had to pick a single series, I’d choose the Red Rising trilogy by Pierce Brown. It does an amazing job depicting how politics really works, the interplay between power and relationships and the clash between different sectors of society, that we see every day in this country. I love fiction because it holds up a mirror to our society.